People with mental health conditions are disproportionately killed by police, and that will only get worse if training programs don't change their priorities

Fair warning that this is an extremely long, research-heavy post. If you want the gist, read the subheadings and bold print text.

25% of people killed by police have a mental health condition

Today, I read a few articles about how people with mental health conditions make up 25% of people that are killed by police. Of course, my immediate response is outrage, but when that passes, I just want to know why. Therefore, I found out why. Take a seat and grab some popcorn, this is going to be outrageous.

Here’s a visual representation of data regarding citizens killed by police collected by the Washington Post in 2015. Dark ones are individuals who are known to have had a mental health condition, and light ones are individuals who were not.

In this data set, 254 individuals with mental illness were represented, making up just over 25% of these fatalities.

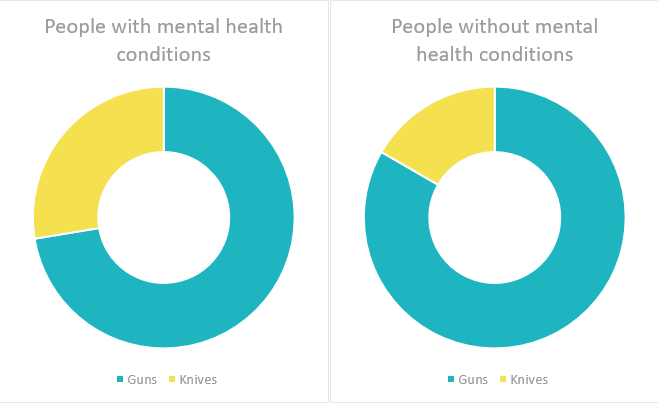

One thing that’s interesting to look at in this data is what prompted use of lethal force for these individuals. The overall data only tracked use of “deadly weapons” versus being unarmed, with a toy weapon, or unknown. When looking at that data alone, it seems like people with mental health conditions are more likely (80.3%) to use a deadly weapon in a lethal force situation than people without them (77%). But that doesn’t tell the whole story.

What’s a deadly weapon?

Yes, technically, knives are considered a deadly weapon. But are they as deadly as guns? Most definitely not. Between 2005 to 2015, only 3 officers were killed with a knife, according to FBI data. They are not likely to die when someone is brandishing a knife. So let’s look at those statistics again, but break it down with guns versus knives.

So this means that people are way more likely to be killed holding less lethal weapon if they have a mental health condition.

Another thing to look at is non-weapon objects that people are brandishing when they are killed by police. While there is a fair share of people without mental health conditions that get killed while holding a pipe, box cutter, or even just a cell phone, that percentage is much higher in people with mental health conditions.

10.2% of people with mental health conditions that were killed were holding a non-weapon threatening object. This could be anything from a metal pipe to a screwdriver to a broom handle to a spoon. Only 5.2% of people without mental health conditions that were killed were doing the same and, most of the time, these objects were in fact far more lethal.

Let’s also examine some other factors here. While people without mental health conditions that were killed while brandishing a gun were shooting at police, in the middle of committing a violent crime, or just refused to stand down, there are different stories for the others.

Suicide attempts tend to get you killed by the police

9.1% of people with MH conditions that were killed were explicitly seeking suicide by cop. Reports of these individuals often say that the victim was pointing a gun and telling police to kill them. So that takes down our number of people that are looking to actually hurt people with their weapons.

Across all weapon types, 29.1% of people with MH conditions that were killed came into contact with the police because either they or someone else called for help, reporting that they were suicidal. In many cases, these individuals were shot and killed because they simply refused to put down the weapon that they were threatening themselves with. In other cases, they defensively brandished their weapon after the police brandished theirs. And in more, the person was in such a state of anxiety, heightened arousal, and psychological distress that they became violent when confronted by police. Which can absolutely be prevented.

Looking at the individual stories is completely disheartening. These situations could have been resolved if police knew what to do. Two people were killed in a confrontation after being reported as a suicidal person outside of a psychiatric treatment facility or hospital. One man, whose weapon status is unknown, was killed after being found with self-inflicted stab wounds and was shot during a confrontation. One was technically armed, but only pulled out his knife after he was shot.

Here’s an excerpt describing one encounter:

Lawrence’s wife and another witness have disputed aspects of that account, saying that Lawrence, while armed, was not advancing and was obviously not in his right mind. Convinced someone was coming to kill him, Lawrence repeatedly asked police officers who they were and what they wanted, his wife said.

“He was clearly confused . . . but they didn’t try to talk to him,” said Lawrence’s father, Bryon Lawrence, who works as an Illinois state prison guard.

“Everyone I work with is a convicted felon; I can’t just go up to them and shoot them,” Bryon Lawrence said. “My boy is 25 years old, working 50 hours a week, paying taxes. He was in his own home when they showed up.

“Within six minutes, they murdered him.”

What I’m saying is that the statistics alone do not really reveal what happens in these scenarios. You might see “person with mental illness lunged at officers with a knife,” but the real story was that a person who wasn’t thinking clearly defended himself against strangers yelling and pointing a gun at him in the middle of his suicide attempt. How does that even happen?

Police aren’t trained to de-escalate crisis situations

I decided to examine the Colorado police training curriculum requirements to see how our officers are trained to handle these situations. These are the requirements that all police academies and other training programs MUST adhere to in order to certify that someone can serve as an officer. This gives a really good picture of how many hours our officers spend learning what, so that we can understand what training they’re coming from when they are called to a crisis scenario.

Here’s the breakdown.

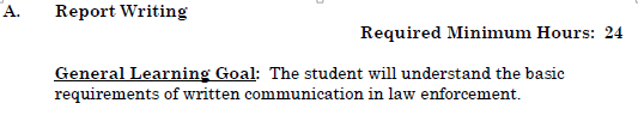

There are 548 total hours in basic police training. It’s divided up into:

- 378 hours of academic learning (69% of training time)

- 62 hours of arrest control training (11.3% of training time)

- 44 hours of driving training (8.0% of training time)

- 64 hours of firearm training (16.9% of training time)

One thing that’s important to note here is that the largest chunk of non-academic, hands-on training is devoted to firearms. Obviously, this training is important. I want my police officers to know how to use their guns. However, they spend more time practicing how to handle guns than practicing how to manage an arrest or handle a crisis situation. There are far more situations in which an officer needs to know how to control an arrest or crisis than there are situations in which an officer needs to use lethal force with a firearm. But, hey, I’ll give you that. They need to know how to use them. That’s fair.

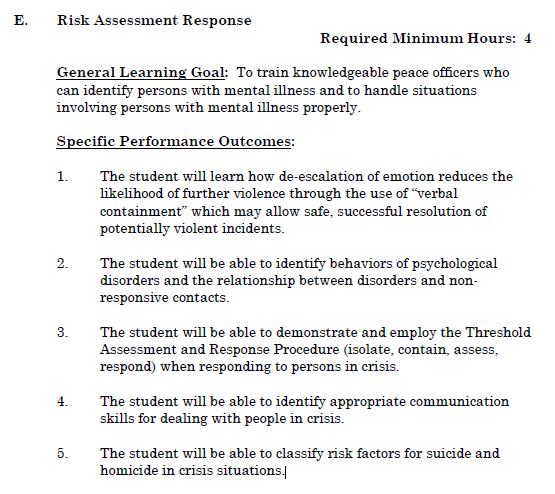

What’s more concerning is the distribution of academic learning time. Despite the fact that an estimated 10% of police-citizen contacts involve mental health crisis, a mere 0.7% (or 4 hours) of learning time is devoted to it. Let’s look at what the learning outcomes are for that tiny sliver of time.

So, just to be clear, in half of a standard work day, police officers are supposed to learn de-escalation techniques, verbal communication skills, a procedure for containing crisis, how to identify people at risk of suicide and homicide, the vast variety of mental health symptoms that they may encounter, and how those symptoms might inhibit a person’s ability to respond to police authority.

People attend college and graduate school for 6+ YEARS to learn all of that. Granted, in greater depth than we expect from police officers, but something that requires a decade of training to master should require more than 4 hours of training to understand on a basic level. For comparison’s sake, helpline volunteers at the Phoenix Center at Auraria are required to undergo a 32 hour training before they are permitted to interact with people potentially in crisis over the phone. Where there is no risk of escalating a situation to the point that lethal force seems necessary.

We should expect more of our public servants than what we expect of college student volunteers over the phone.

Four hours might be all that they can do, right?

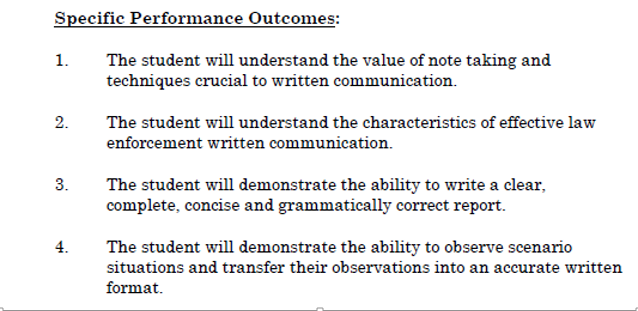

Wrong. Officers are required to spend an equivalent amount of time learning about proper attire, posture, attitude, and demeanor in courtroom appearances. They are required to spend 6 times as much time doing resistance training and aerobic exercise. They are required to spend 6 times as long learning how to fill out paperwork. No, really.

Police training priorities are seriously misplaced, and DUI enforcement is a great example of that

These are just a few examples of misplaced priorities, but I think DUI enforcement is one to pay attention to. Officers are required to spend 6 times as long learning about this. If they’re spending that much time on it, that probably means it takes up more time than crisis intervention, right?

These statistics were honestly hard to find. They aren’t representative of the entire country because, for whatever reason, it isn’t really tracked. There’s a lot of big scary numbers like 1/3 of all traffic fatalities involve alcohol, but that doesn’t really tell me what I want to know. How many people the police interact with are driving while intoxicated?

The most recent data available from the Bureau of Justice Statistics says that an estimated 42% of police-citizens interactions are due to traffic stops. So, obviously, traffic stops are something police need a great deal of training on, but DUI specifically? Not so much.

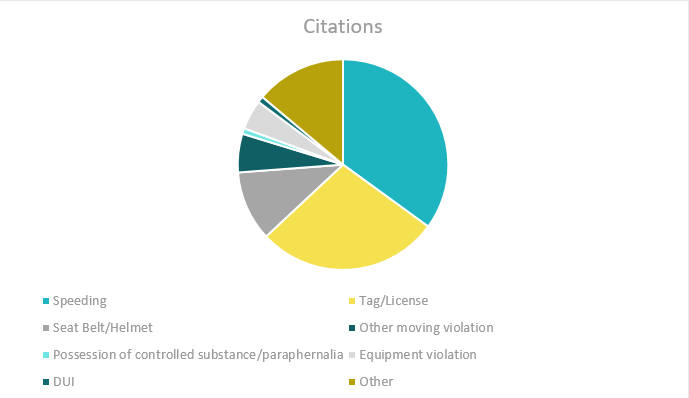

I found one data set collected by Tennessee that counts all citations issued by the TN Highway Patrol each year. The most recent data available is from 2008, which isn’t great, but it’s what I have to work with. In that year, there were 337,415 citations. Here’s how that breaks down.

The biggest clusters of offenses are:

- Speeding (35%)

- Expired/missing tags, expired/missing registration, and driving on suspended/revoked/restricted/improper/no license (28%)

- Other, including various CDL-specific violations as well as vehicular manslaughter, resisting arrest, child endangerment, aggravated assault and other various offenses (14%)

- Seat belt/motorcycle helmet violation (11%)

Notice those two teensy tiny little slivers there? One is possession of controlled substances or paraphernalia (1%) and the other is DUI/DWI (1%).

1% of traffic citations in that year were DUI. ONE. Okay, so maybe Tennessee isn’t an average state. Even if it is, this is only one agency within the state, so the statistics could be way off. Fine, let’s go with that. Even if the actual numbers are ten times this, it’s still only 10% of traffic encounters. Which is only 4.2% of all police-citizen encounters. Assuming this slice of data is representative, it’s more like half a percent.

Not convinced? Well, here’s some more data. Statistics from the Illinois Department of Transportation spanning 5 years showed that, in most counties included, the number of DUI citations issued from DUI checkpoints, which are explicitly set up to catch impaired drivers, was less than 10%. Some counties were in the 2-3% range. The rest were expired tags, broken lights, license issues, etc. Keep in mind that the citations issued at these checkpoints, by the nature of the set up, cannot include speeding or many other moving violations that take up a huge proportion of that pie chart up there. I think this validates our original data set as fairly representative. DUIs just aren’t a huge chunk of police activity.

If <1% of all police encounters involve DUI and 10% involve mental health crisis, why are police training programs spending 6 times as much academic learning time on DUI versus crisis intervention?

The short answer is money.

According to this fun informational piece published by the Colorado Department of Transportation, the cost of getting a DUI MINUS insurance fee increases, attorney fees, and other personal expenses, is about $4500. That’s jail fees, fines, supervision fees, etc. That’s a hunk of money, that is. I can see why there’s such a motivation to catch DUI offenders, because that earns the state a decent amount of money for a fairly minimal amount of officer time/wages.

What does crisis intervention earn? Absolutely nothing. It costs police departments a hell of a lot. A crisis intervention call might be a 6 hour ordeal of de-escalation, connecting to resources, transporting someone to treatment, and dealing with documentation. You can be sure they aren’t doing it alone.

So let’s assume that 2 officers making the hourly median wage of $32.37 use up 6 working hours dealing with a mental health crisis call. That’s almost $400 in labor alone. That’s 6 hours of time not writing tickets, the fines from which help keep the department going. That’s 6 hours of time that could have a lasting emotional impact on the officer, eventually requiring therapy and potentially FMLA leave. That’s 6 hours of work that officers really just shouldn’t be doing anyway, but they have to because hospitals and outpatient services have been closing right and left for years.

With steep budget cuts and ACA repeal looming on the horizon, this situation will probably only get worse, not better

More people will find themselves unable to afford the care they need to avoid going into crisis. More people will find themselves booted out the door of a psychiatric hospital too early because they are out of days for the year. More people will end up frantically calling 911 because they think they might try to harm themselves, then wind up dead when a terrified police officer pulls the trigger.

Unless there’s a solution. And aren’t we in luck?

There is a solution, it’s just underutilized and underfunded

Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training, otherwise known as the Memphis Model, is a supplementary curriculum for police officers that trains them to interact with people experiencing mental health crisis. Here’s a general overview of what CIT training involves:

- Mental Health Didactics: basic lectures on what the different mental health conditions are, how they are treated, and how they can affect functioning along with information about the civil rights of people with mental illness and how involuntary mental health holds work.

- Community Support: information about community support services available to people with mental health conditions, presentations by people who have mental illnesses to provide exposure and give insight into living with mental illness, presentations on cultural, racial, ethnic, and sexual and gender identification issues and mental health, and special issues with homeless and veteran individuals.

- De-Escalation training: hands-on skills training and role playing for de-escalation in crisis intervention, including verbal and non-verbal skills as well as methods for safe escalation if de-escalation is unsuccessful.

- Site visits: visits to mental health facilities, homeless shelters, state hospitals, drop-in centers, and outpatient treatment facilities to facilitate interaction between trainees and people with mental illness.

- Law Enforcement: training on issues related to legal liability, safety, and department policy when it comes to mental health crisis situations as well as stress and health management techniques for the officers

- Research and Systems: information about the research supporting CIT programs as well as an overview of diversion strategies and mental health courts.

In summary, officers are not just trained to use de-escalation techniques, but they’re exposed regularly to the very people that they sometimes wind up killing out of fear. It’s 40 hours long, which is longer than they spend learning how to fill out paperwork and do field sobriety tests. As it should be.

So, what’s the problem? Well. Not a whole lot of officers get to take this training. In some counties, the program doesn’t exist at all. Here’s a map of Colorado with participating counties darkened.

Even in these counties, CIT isn’t exactly standard. Take Jefferson County, my home. Their website says that the program “selectively recruits” “a number” of officers. Which means there probably aren’t enough of them to go around. And “selectively recruits?” You know that means they are investing in the best officers they feel are best suited for CIT. Unfortunately, they’re the ones that need it the least. Officers that are terrified of people with mental health conditions, struggle with de-escalation, and seem a little trigger-happy are the ones that should be here, not just the cream of the crop.

Arapahoe seems to be doing better. Their website says 80% of their officers are trained, which is great. It also says the goal of the Colorado CIT program is to have 25% of LEOs trained in the state. Well, that’s a bummer.

If you’re having a crisis, our state’s goal is for you to have a 1 in 4 shot at getting an officer that knows what to do. And if you’re in one of the 49 counties without CIT at all, well, you’re just out of luck entirely.

Does it actually work? Can CIT training prevent officers from using lethal force?

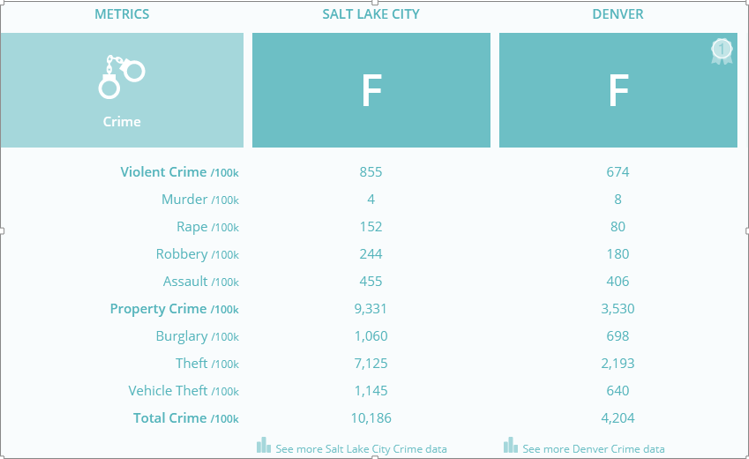

Yes. Absolutely. The Salt Lake City Police Department has embraced these techniques department-wide. Guess what? They haven’t killed anyone, mental health condition or otherwise, since September 2015. After a series of officer shootings that drew criticism from the community, the department revamped their training, dedicating a quarter of their training time to de-escalation techniques.

And if you’re thinking, “well, it’s Utah. It’s smaller, their crime rate is probably pretty low, maybe the police don’t need to use lethal force,” you’re wrong. Salt Lake City has more than twice as much total crime per 100,000 people than Denver does (but we aren’t doing so great either).

So, no. If anything, they have a greater need to use lethal force. But they don’t. Because de-escalation means not killing innocent people, not agitating people in crisis, and administering justice and enforcing the law fairly.

Routinely executing people who can be taken into custody, given a punishment, and possibly rehabilitated is completely absurd, but we accept it as something police just “have to do.” Salt Lake City is proving otherwise, and Colorado should take a hint.

How do we change this?

This is a lot of information, I know. There are a lot of moving pieces in this issue and it’s hard to pin down what to do. So here are my recommendations.

- Advocate for police training time allocation that accurately reflects the demands of the job. Right now, training time seems to be distributed according to what is perceived to be most important. That shouldn’t be the case.

- Advocate for universal CIT training for ALL officers in Colorado before they even touch a gun. No “selective recruitment” of the best officers and no making the training voluntary. If you want to serve as a peace officer in this state, you should know how to de-escalate and create peace. Period.

- Put serious pressure on police departments to thoroughly investigate officer shootings and raise the standards of what is considered “justifiable” use of lethal force. The standard should be “absolute necessity in order to survive,” not “feeling threatened by a kitchen knife.” Again, less than an officer a year dies from a knife wound. It shouldn’t generally justify use of lethal force.