Welcome to Part 3 of our educational series on Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT). Lots of advocates for recovery-oriented care were upset that the Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act incentivized states with AOT programs and let out a cheer when that was rolled back to simple increased funding. I, however, am not happy about it. I think the practice should be discontinued entirely. In the second part, I talked about how it casts doubt on our reasoning capacity. This time, I’m going to talk about how its justification as a preemptive least restrictive alternative is faulty. Why?

AOT doesn’t reliably prevent re-hospitalization or arrest.

The idea of “least restrictive alternative” is a legal concept that most states have adopted in order to best protect the liberty and dignity of people subjected to involuntary psychiatric treatment. It means that someone who is being treated against their will must be treated in the least restrictive setting possible to meet their needs. AOT operates on the principle that involuntary outpatient medication orders are inherently less restrictive than the hospitalization or arrest that will result if someone is left unmedicated. That’d be true if it actually prevented hospitalization or arrest. But it doesn’t.

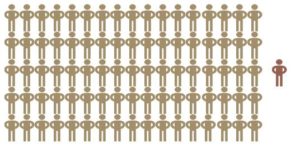

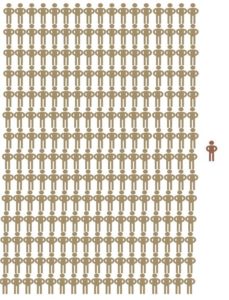

Only TWO randomized controlled trials of AOT programs have been conducted and “neither provided definitive evidence that [the orders] are in themselves efficacious” in improving rehospitalization and arrest rates. A statistical review of the pooled data from those studies estimated that 85 people would need to be in AOT to prevent one hospitalization and 238 people would need to be in AOT to prevent one arrest (Lambert, et al. 57). Just visualize that for a second.

Here’s 85 people under an AOT who didn’t get rehospitalized, and one guy that did.

Here’s 238 people under an AOT who didn’t get arrested, and one girl that did.

Ridiculous.

Some people argue “well, it’s hard to get randomized controlled trials of AOT, you shouldn’t rely on those.” Fine. A meta-analysis of five studies with various methods and over 1100 participants found “no statistically significant difference in readmission rate” either (Kisely, et al. 7-8). The UK’s National Health Service advisor that recommended AOT has changed his mind because he hasn’t seen any proof that it actually works (Manning).

Why are we still doing it if there’s no proof that it works? I think it’s mostly to soothe misplaced public fear about the dangerousness of people with psychosis, not to actually practice good medicine or help people. More on that later.

Sources:

Kisely, Stephen, Leslie Ann Campbell, Anita Scott, Neil J. Preston, and Jianguo Xiao. “Randomized and non-randomized evidence for the effect of compulsory community and involuntary out-patient treatment on health service use: systematic review and meta-analysis.” Psychological Medicine. 37 (2007). 3-14. Web.

Lambert, T. J., B. S. Singh, and M. X. Patel. “Community Treatment Orders and Antipsychotic Long-acting Injections.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 195.52 (2009): n. pag. Web.

Manning, Sanchez. “‘Psychiatric asbos’ were an error says key advisor.” Independent. Independent.co.uk. 13 April 2013. Web.